Two-Lane Blacktop shares much in common with Vanishing Point, the subject of the first film I reviewed in this series. Released in the same year, 1971, TLB also features an unconventional narrative aimed to pique the interest of the then-burgeoning counter-culture audience in America; and like Vanishing Point, its lack of a strong plot helps it to transcend the hallmarks of the car-movie genre. As such, it is a film that likely could never be made today.

Two-Lane Blacktop shares much in common with Vanishing Point, the subject of the first film I reviewed in this series. Released in the same year, 1971, TLB also features an unconventional narrative aimed to pique the interest of the then-burgeoning counter-culture audience in America; and like Vanishing Point, its lack of a strong plot helps it to transcend the hallmarks of the car-movie genre. As such, it is a film that likely could never be made today.

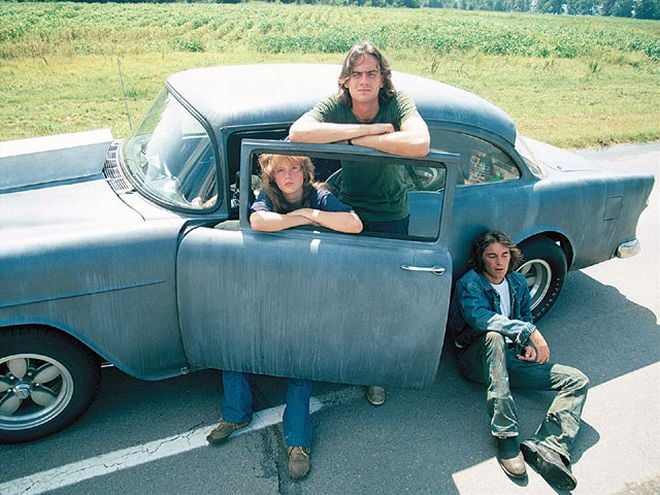

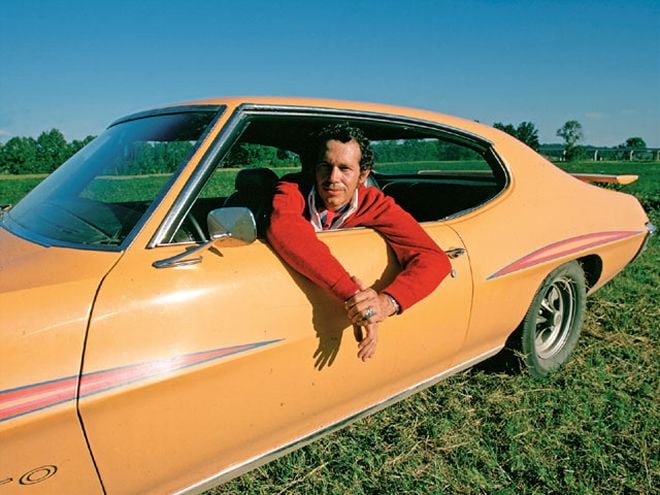

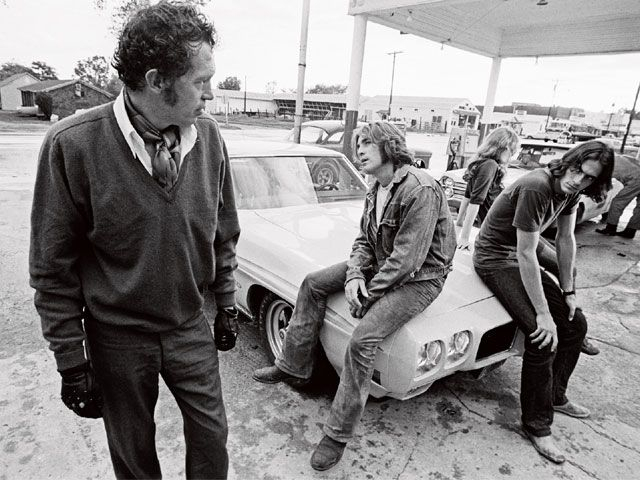

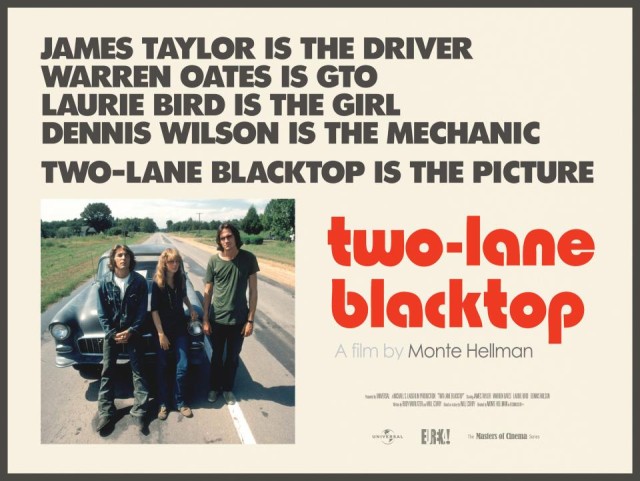

Released by Universal Studios and directed by Monte Hellman, Two-Lane Blacktop can begin to be considered unique by it’s casting of non-actors in three of the films’ four primary roles. Singer-songwriter James Taylor plays The Driver, the film’s main protagonist. Beach Boys drummer, the late Dennis Wilson, plays The Mechanic, and Laurie Bird portrays The Girl. Only Warren Oates, in the iconic role of G.T.O., was a seasoned actor at the time of the film’s production.

Left: Laurie Bird, James Taylor and Dennis Wilson, as The Girl, The Driver, and The Mechanic. Right: Warren Oates as G.T.O.

What little of a plot that exists in Two-Lane Blacktop concerns the nomadic wanderings of The Driver and The Mechanic as they go from town to town entering their rodded 1955 Chevrolet in amateur drag races for money.

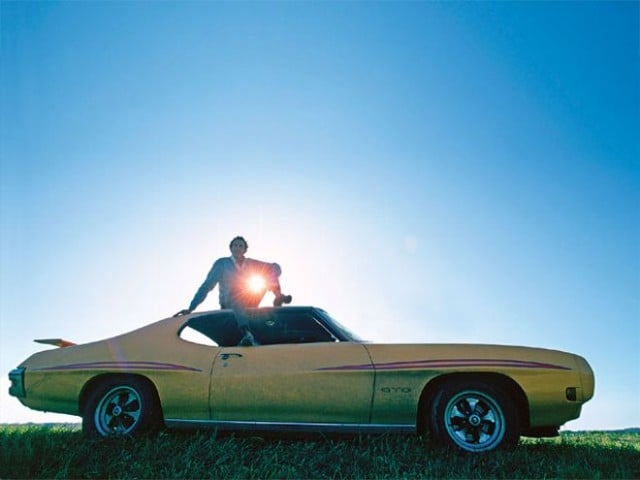

Their rootless existence puts them on a collision course with The Girl, a teenage, hitchhiking hippie, and G.T.O., a middle-aged, corporate establishment rogue who, through some sort of tragic loss, has been reduced to a listless, pathological liar roaming the country in a 1970 Pontiac G.T.O. Judge. These peoples’ critical mass results in a planned cross-country race along Route 66 for pink slips with no definitive finish line.

What the film lacks in plot it makes up for in character detail and themes. While all of the central characters interact with one another, they do so loosely, and without firm bonds and without consequence of heart.

The Girl, for example, becomes romantically entwined with all three male protagonists, yet asks nothing of any of them, and receives even less. The Driver and The Mechanic, seemingly long time friends, never even share a joke or warm moment throughout the film.

Most noticeably, the rivalry between G.T.O. and The Driver and The Mechanic, is nebulous and is never resolved, much less defined. It vacillates between aggression and camaraderie, and sometimes both in the same scene.

All of this represents the thematic crux of the film, that these people represent a microcosm for America at the time of the Vietnam War: a scarred and divided nation, adrift and unsure of its existence and direction.

The Driver, The Mechanic, and The Girl clearly represent the left-wing, anti-war youth movement of America idealized in such historical groups as the S.D.S. and the Weather Underground, and G.T.O. represents The Man, the conservative, materialistic and status-obsessed generation that preceded them.

The character’s thematic roles are literally mirrored by the clothes they wear, the cars they drive, and the goals they have. All of this sub-content is deftly handled by Hellman’s fine direction and is never heavy-handed or over-the-top. It is this infusion of thoughtful social comment that really separates the film from others of the genre.

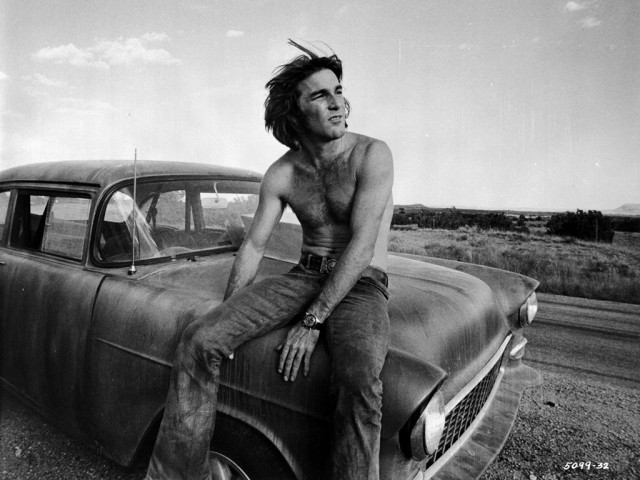

As for the film’s cars there are exquisite examples of American muscle throughout. The main protagonists’ ’55 Chevy is battered and covered in dull gray primer, and represents the DIY, counter-culture ethic espoused by its occupants.

It features a normally aspirated, tunnel-rammed 454 big-block, M-22 Muncie Rock Crusher four-speed with straight-cut gears, ’60s Olds posi-traction rear, a gasser-style black interior and fiberglass front end, doors, hood scoop and trunk lid.

In contrast to this, their opponents’ cars are all dotingly cared-for, glossy hot rods, most notably G.T.O.’s Pontiac GTO, an Orbit Orange Judge with Keystone Klassic wheels, eyebrow stripes and spoiler, but curiously no Judge decals. Other cars in the film that put in brief appearances include a 1970 Hemi ‘Cuda, a 1932 Ford hot rod with a 427 ci big-block crammed in it, a 1968 AMC Javelin, and various and sundry Camaros, Challengers, and Mustangs littering the background of many of the drag racing sequences.

If you are looking for an archetypal car movie full of chases, races, and accidents, perhaps you might want to pass on Two-Lane Blacktop and seek lighter fare, as this film is more of a character study and art film than it is a smash ‘em up actioner.

But it is the very artfulness and subtlety of the screenwriting and direction that makes TLB a thoroughly engaging and enjoyable film. It doesn’t ask too much of you, but it doesn’t ask too little either. I rate Two-Lane Blacktop a solid eight out of ten cylinders.

About The Author: Rob Finkelman is a freelance writer for Street Muscle Magazine. He attended and graduated from New York University’s film school in 1992, and subsequently worked in the movie business for twenty years as a documentarian and screenwriter. Combining his two great passions in life – films and cars – and writing about them is a dream job for him. He will be bringing us a Car Movie Review each month, and he’s open to suggestions so list yours below.